Medusa: Reclaiming the monster within

The silenced sound of forbidden power and how to find your lost voice

Before we dive into today’s post, I have some quick exciting news to share. In case you haven’t heard, our upcoming game Echoes has smashed its funding target and is available for pre-order on Kickstarter. It’s my absolute favourite project because it combines Jungian archetypes, tarot and time travel in a mysterious, futuristic setting. I love working on it and think you’ll love playing it.

Now, onto Menaces of the Mind Part III. You can watch the post on YouTube or read it below.

***

They say her gaze turned others to stone, but what if, just once, Medusa had been truly seen?

This third part of Menaces of the Mind series is a how-to for reclaiming your inner Medusa and a deep dive into why we all really, really ought to do just that.

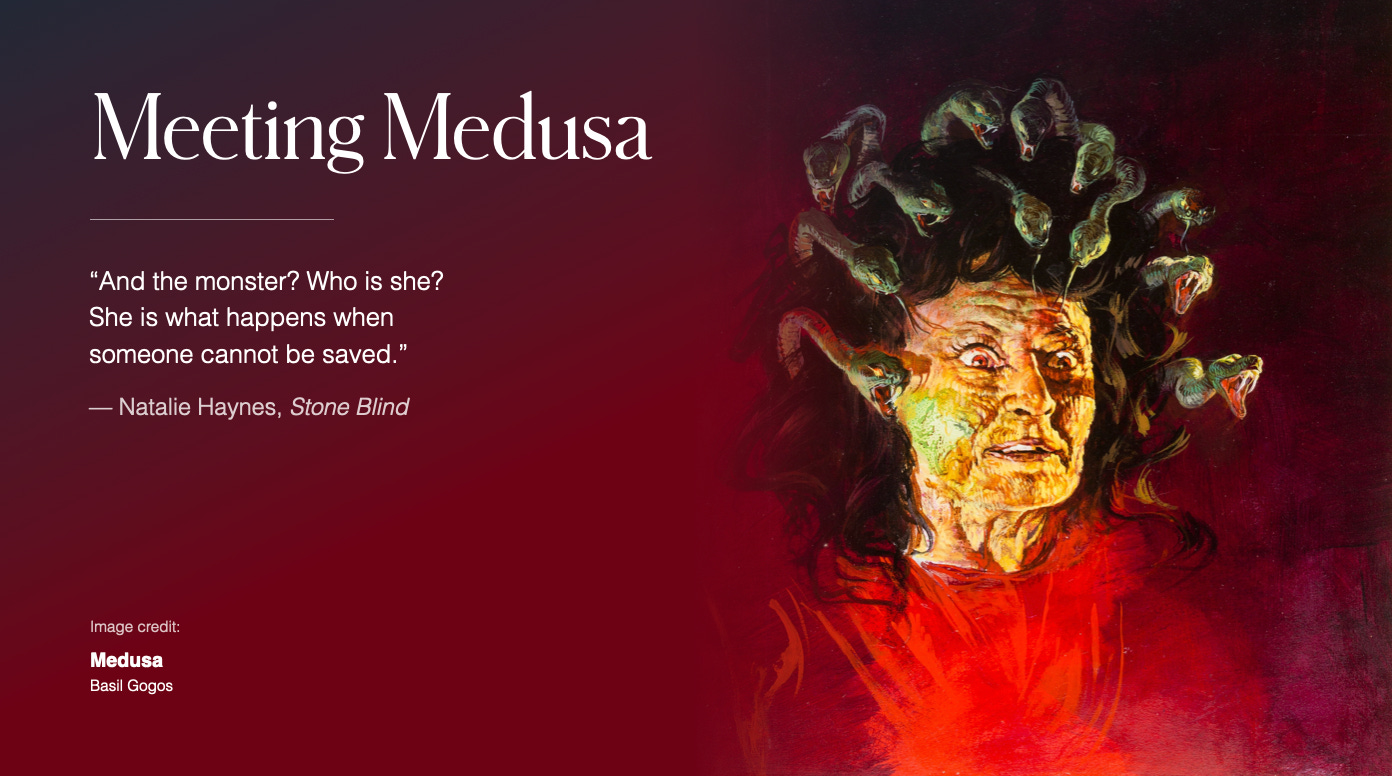

Medusa

Medusa is one of the most recognisable monsters in all mythology, with snakes for hair, a petrifying gaze, and a mien so powerful that even after death, it could destroy.

But before she was a monster, Medusa was a maiden – the only mortal among the three Gorgon sisters. She served as a priestess in Athena’s temple, sworn to celibacy until she lay with Poseidon, the god of the sea, consensually or not, depending on the version of the story you read. Either way, though, the outcome is the same: Medusa is the one to be punished.

For her transgression, Athena transforms her into a creature so terrifying that no one could look at her without turning to stone. Medusa's metamorphosis takes her from beautiful to monstrous, from visible to unbearable. From desirable to unseeable.

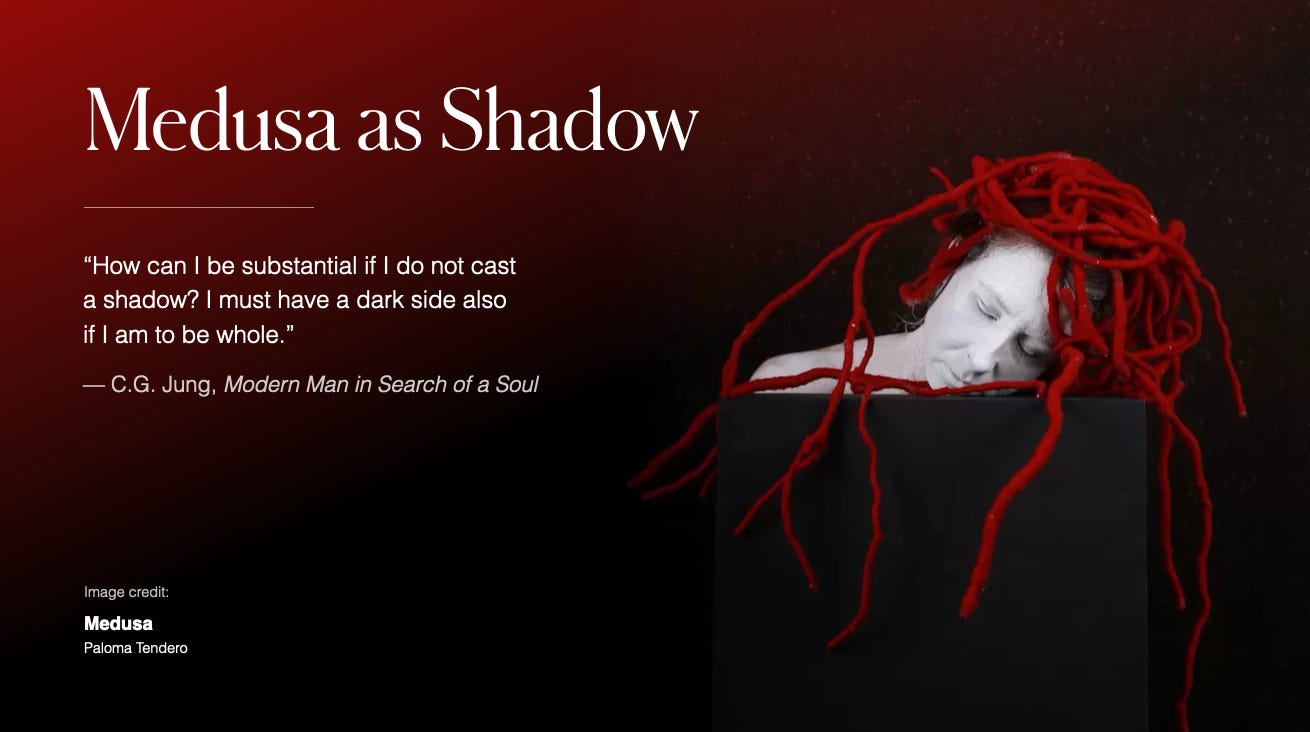

Medusa as shadow

“How can I be substantial if I do not cast a shadow? I must have a dark side also If I am to be whole.”

― C.G. Jung, Modern Man in Search of a Soul

Medusa is, in many ways, the quintessential shadow figure. She represents the aspects of self our culture cannot easily tolerate – truths too raw to be neatly expressed, namely: feminine power, feminine sexuality, feminine rage.

In patriarchal cultures, women’s anger is taboo. It’s considered unattractive, dangerous, “too much.” As a result, women and girls are conditioned to internalise our anger from a very young age – to turn it inwards, and direct it towards ourselves rather than others. When we do this, that rage calcifies into shame, anxiety, depression, or physical illness. Something, in other words, that will stop us in our tracks.

But this archetype of course isn't only for women to worry about. Medusa’s gaze turns men to stone, too, because that's what internalising pain, anger and needs does to all of us: it freezes, paralyses, leaves us petrified — emotionally, psychologically, even spiritually.

In other words, anyone denied the right to express pain, anger, power or any other kind of innate, emotional force may well find their inner Medusa turning to face them.

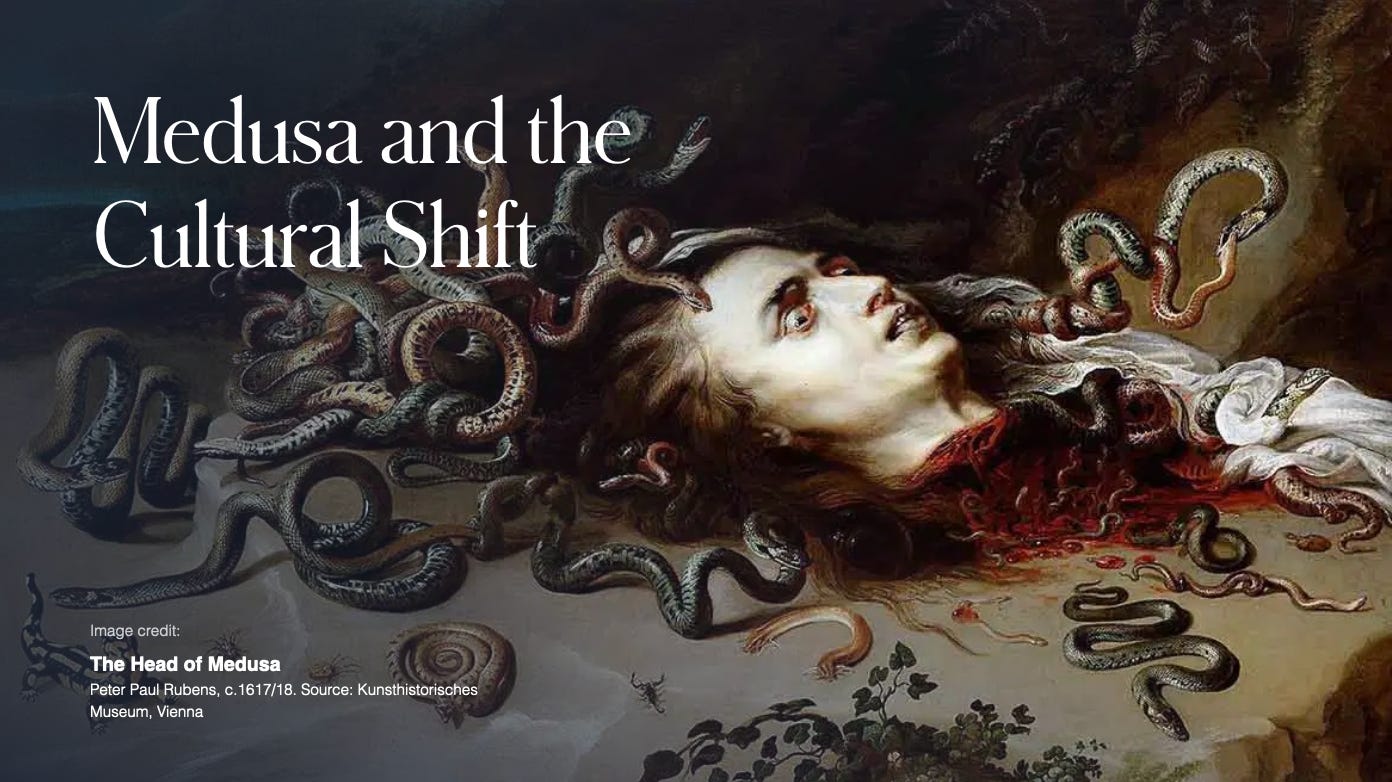

Medusa & the Cultural Shift

Let's rewind back to the beginning, because the context of this story's origin is illuminating. Medusa's tale emerged during a time of great change to the collective experience of humankind. Largely matrilineal societies – settlements where nature, the earth, and goddesses of fertility held great sway – were being replaced by the patriarchal cultures of nomadic communities, followed by hierarchies, and then civilisation as we know it.

During that shift, the feminine — that is, a psychological principle that has to do with receptivity, intuition, emotion, relationships and the implicit — was forced underground; superseded by the masculine values of goal-orientation, rational thinking and the explicit.

So, earth goddesses were downgraded and the moon gave way to the sun. As this happened, intuition and mystery were replaced by linearity, order, and control.

And of course this pattern isn’t just ancient history – it lives on even today. Every time a woman swallows her anger to avoid being called “difficult,” every time someone hides their intuition in favour of logic because it seems safer, every time a person of any gender learns to mistrust their emotions in order to survive in a goal‑driven, productivity‑obsessed world, that old silencing plays out again.

Medusa stands at the edge of that particular fault line and her story depicts the objectification and demonisation of femininity and women – this important figure is punished not only for being sexual or powerful, but for being seen in those ways. She was literally dehumanised for being beautiful, desirable, and for what was done to her, whether she chose it or not. But – and this is so important – Medusa doesn't end when slain; her power – primal and indestructible – cannot be snuffed out by a pesky little beheading.

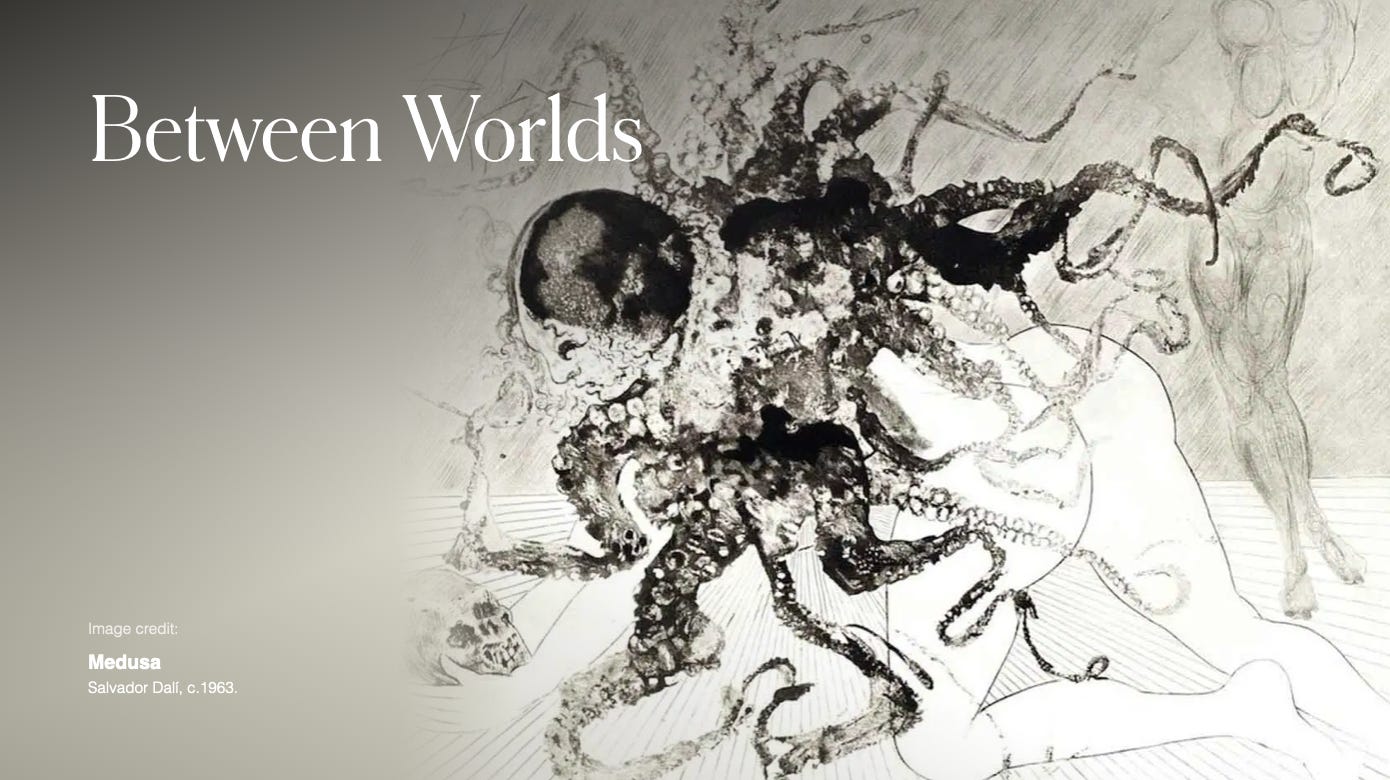

Between Worlds

What she becomes, then, is a liminal figure who, like all monsters, serves as a bridge between worlds. She’s human and animal. Mortal and divine. Her hair is a nest of snakes, which are symbols of both death and transformation. She is tangled, contradictory, and sacred in her complexity.

Importantly, she is cast out by Athena: the virginal goddess of wisdom, strategy, and war. Literally born from Zeus’ head, Athena represents logic and order in feminine form. She is the face of femininity shaped to fit a patriarchal ideal – severed from wildness, instinct and vulnerability.

So, where Medusa is chaos, Athena is order – a classic story of demonised yin vs. exalted yang, and all going on within the bodies of women.

Medusa shows us what happens when feminine energy is repressed, and my favourite detail from the entire tale is this. Whether consensual or not, Medusa lies with Posiedon, god of the sea – turbulent, wild, unpredictable, dangerous and unstoppable – and this is too much for Athena (i.e. civilisation) to bear. Medusa, as a result of this coupling, is stepping back into the frightful feminine forces of chaos, depth and the unknown. She is punished, then, not just for the act, or for her beauty, but for consorting with the unconscious, where taboo feminine power resides.

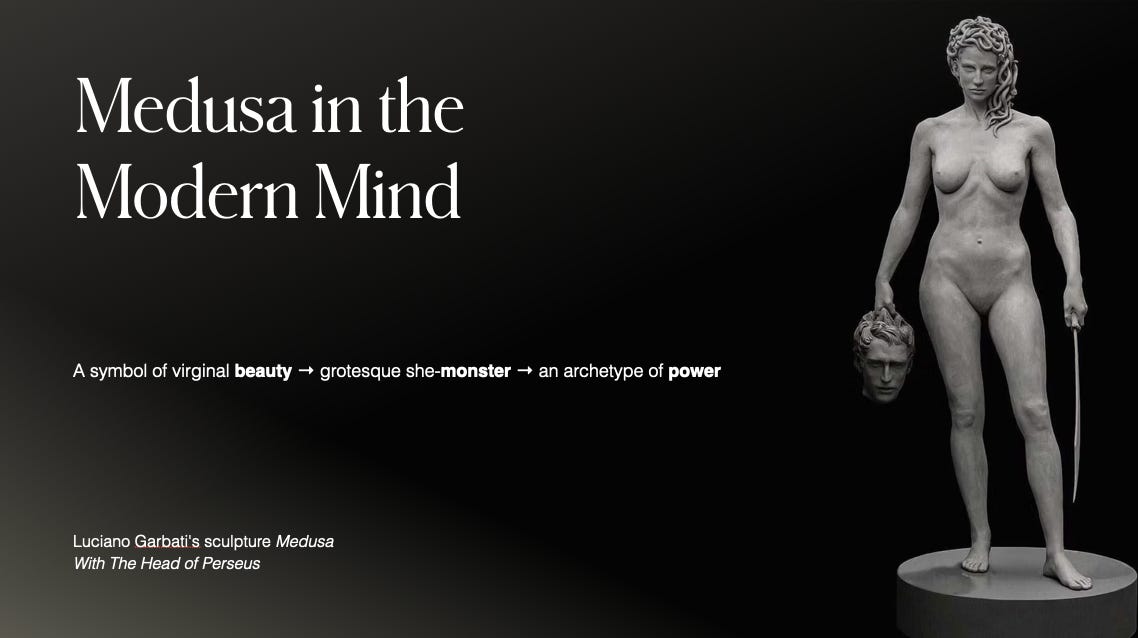

Medusa in the modern mind

This gives me chills, and I'm not the only one. After centuries of being seen as a grotesque, fearful figure, Medusa, more recently, has been reclaimed as a symbol of feminine agency.

Luciano Garbati's Medusa statue in New York, for example, stands as a powerful symbol of the #MeToo movement, particularly among survivors of sexual assault. It reimagines the Medusa myth by portraying her as a figure holding the head of Perseus, inverting the traditional narrative where Perseus is the hero who slays the monster.

So, she's transformed once again: from a symbol of virginal beauty to a grotesque she-monster to an archetype of power. She is an eternal reminder that no matter how disempowered we might feel, our strength does not disappear; it just goes underground until we dare to bring it back.

The Integration of Medusa

Let’s talk briefly about the "hero" of Medusa's story: Perseus.

Perseus is sent to slay Medusa, but of course he can't face her directly, not without being turned to stone. So he holds up Athena’s gift: a polished shield, which serves as a mirror. Then, through reflection rather than confrontation, he beheads her.

The psychological meaning of this motif is as clear as any. Sometimes, looking straight at repressed pain or other unconscious content will overwhelm us. But if we can reflect on it – through writing, dreams, art or connected conversation – we can integrate what was once too dangerous to face.

Even Jung warned against staring directly into the unconscious – better, he proposed, to observe its movements in the water, in dream, in symbol and story, just as we're doing in all of these articles. Perseus succeeds where others fail by renouncing brute force and, instead, respecting the power of what he faces.

Importantly, that power does not die when Medusa's body is slain. Her severed head continues to destroy tyrants and monsters even after death. Finally, in a beautiful metaphor for psychological integration, Athena – the same goddess who cursed her – emblazons Medusa’s image onto her breastplate (or shield, depending on the story's version) where it's used for protection.

The monster, in other words, becomes the medicine.

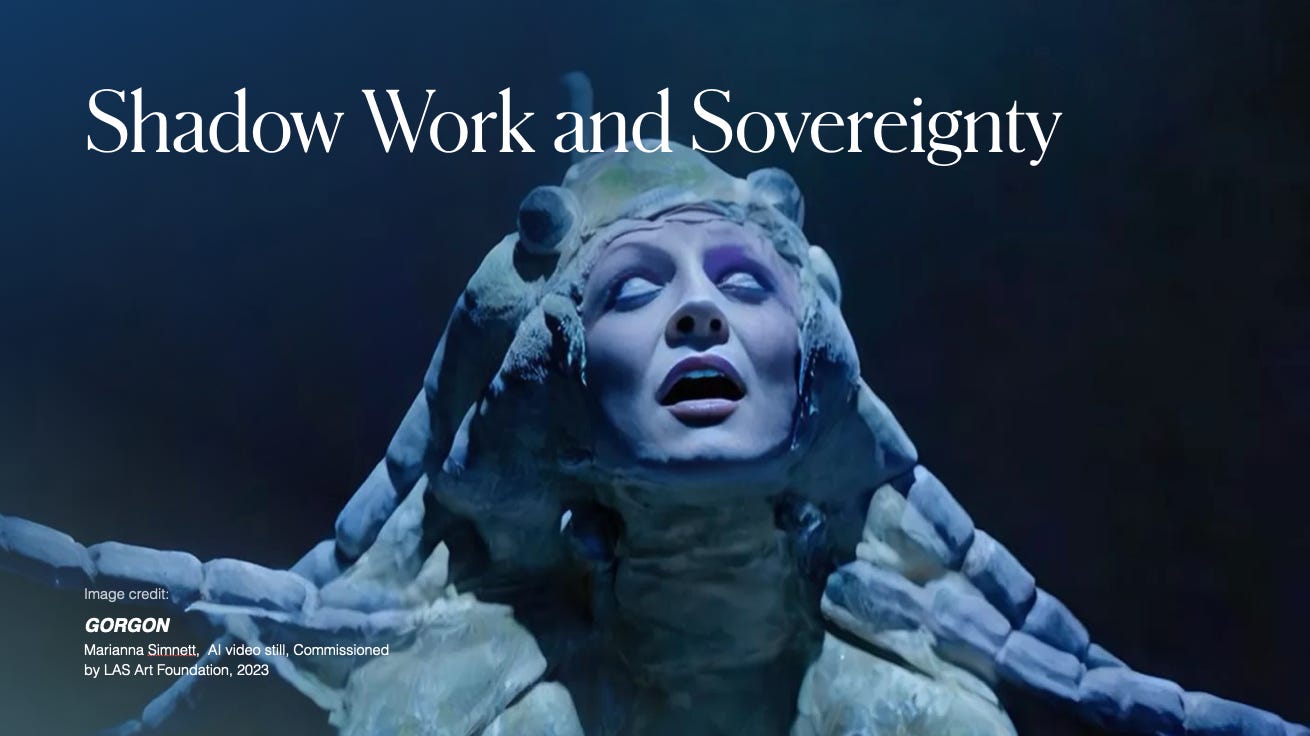

Shadow Work & Sovereignty

So, this is what integration promises. When we reclaim what we once exiled – be it our anger, our needs, sexuality, voice, power, or whatever – it stops appearing as an ugly, monstrous threat. Instead, it strengthens us.

If we don't accept this challenge, then, just like Medusa's power, those parts will be forced to rumble away menacingly from the shadow. They will show up as symptoms and illnesses, and they will get projected out onto the world around us too.

“The psychological rule says that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate.”

Carl Jung, CW9, Part I: Archetypes of the Collective Unconscious

Put differently, if we don’t face our inner Medusas, we’ll keep meeting them out there in real life — as conflict, as threat, as pain, as the paralysing anger of others.

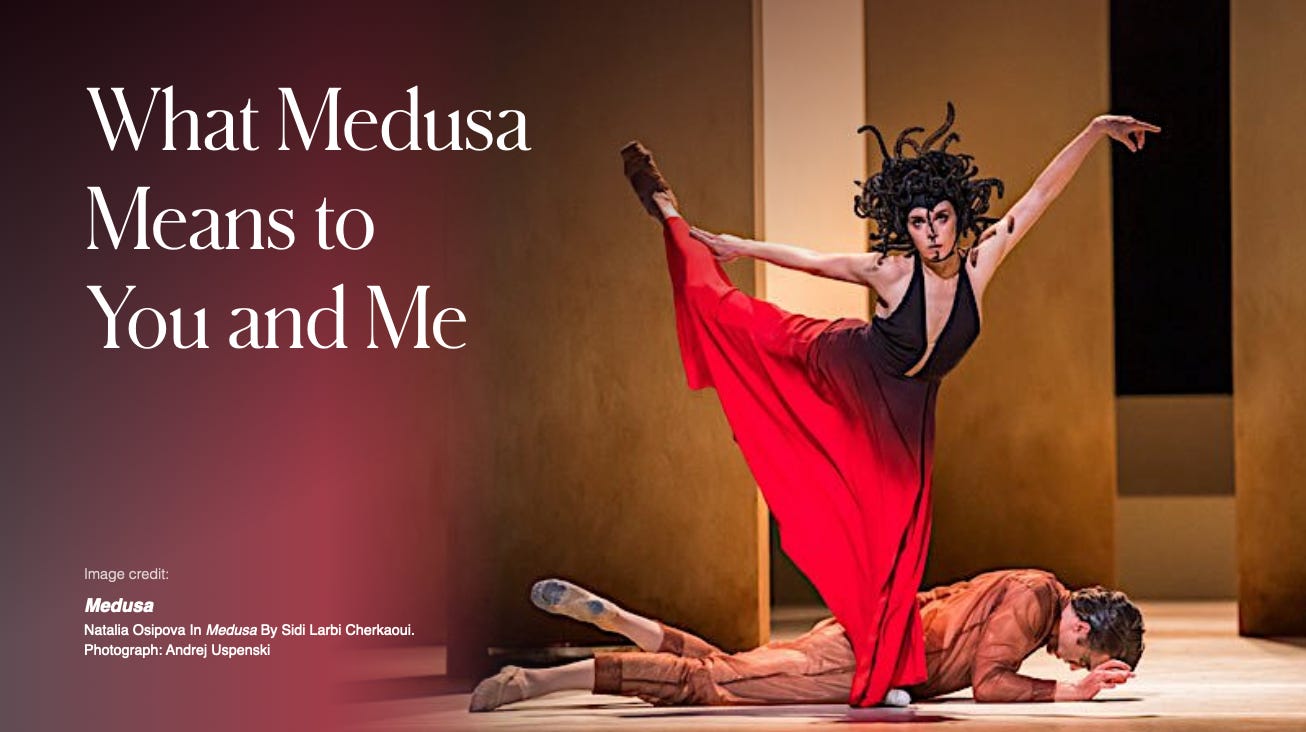

So what does Medusa mean for you and me?

So, how can we break this pattern? How do we brave a look at Medusa's terrifying face as Perseus did?

Of course the answer to this question will be different for different people, and it will depend on what we've tried to shut out over the years. Whatever our unsightly monsters are made of, it's important not to rush in, guns a-blazing, but to do as that clever young hero did and seek these entities through careful reflection.

Reclaiming your Medusa may mean revisiting moments when you were silenced. Moments of injustice. Moments when your own thoughts, feelings, perception of the world — your truth — was denied. It may mean daring to speak up, to lift your chin or stand taller in the face of what's expected of you.

Regardless of whether you feel shame over your body, your appearance, your emotions, sexuality, natural instincts, opinions or story, Medusa's gift is the all-important reminder that there is power within all of these things. If used consciously and with acceptance, then you can bring the lost parts of yourself back from the brink, and they can fight alongside you, as opposed to against you.

Perseus went on to save Andromeda, the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia, from a sea monster, of all things. He brought something pure and beautiful back from the chaotic unknown, and you can too.

Next time, we're going to meet the Vampire within – charming, seductive, addictive. Until then, let a part of your mind stay with the mesmerising monster Medusa so that she can teach you her most poetic lesson: sometimes, the things you were told to hide may be the very things that will save you.

References & Citations

This Jungian Life Podcast, ‘The Many Faces of Medusa’

Carl Jung, ‘The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious’

Carl Jung, ‘Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self’

Clarissa Pinkola Estés, ‘Women Who Run With the Wolves’

Marie-Louise von Franz, ‘Shadow and Evil in Fairy Tales’

Ovid, ‘Metamorphoses’

Natalie Haynes, ‘Stone Blind’

I love women reclaiming the power of Medusa through tattoos (it might be my next one). I also love how Medusa is connected to feminized writing (ecriture feminine) in Helene Cixous's "The Laugh of the Medusa." She can be such an empowering figure.

I started doing rituals with her. I have a Medusa line of rings that I've designed.