The Chimeric Self: Embracing the beauty of contradiction (Menaces of the Mind #11)

A monster of many faces – this is why wholeness is messy

You can listen to this post on YouTube or read it below.

***

It moves like a nightmare stitched from four different dreams: a lion with a goat’s head rising from its back, a dragon’s wings, and a serpent tail that hisses and bites. The Chimera is not one beast but many – a living contradiction that transgresses boundaries of species, type, and reality. And that world-rattling horror is exactly why it can be so profoundly helpful to us.

So, let’s invite this beast to the table and see what it has to say.

This article is for anyone who’s ever felt pulled asunder by disparate parts of themselves. In other words, all of us.

The Chimera – Monster of Contradiction

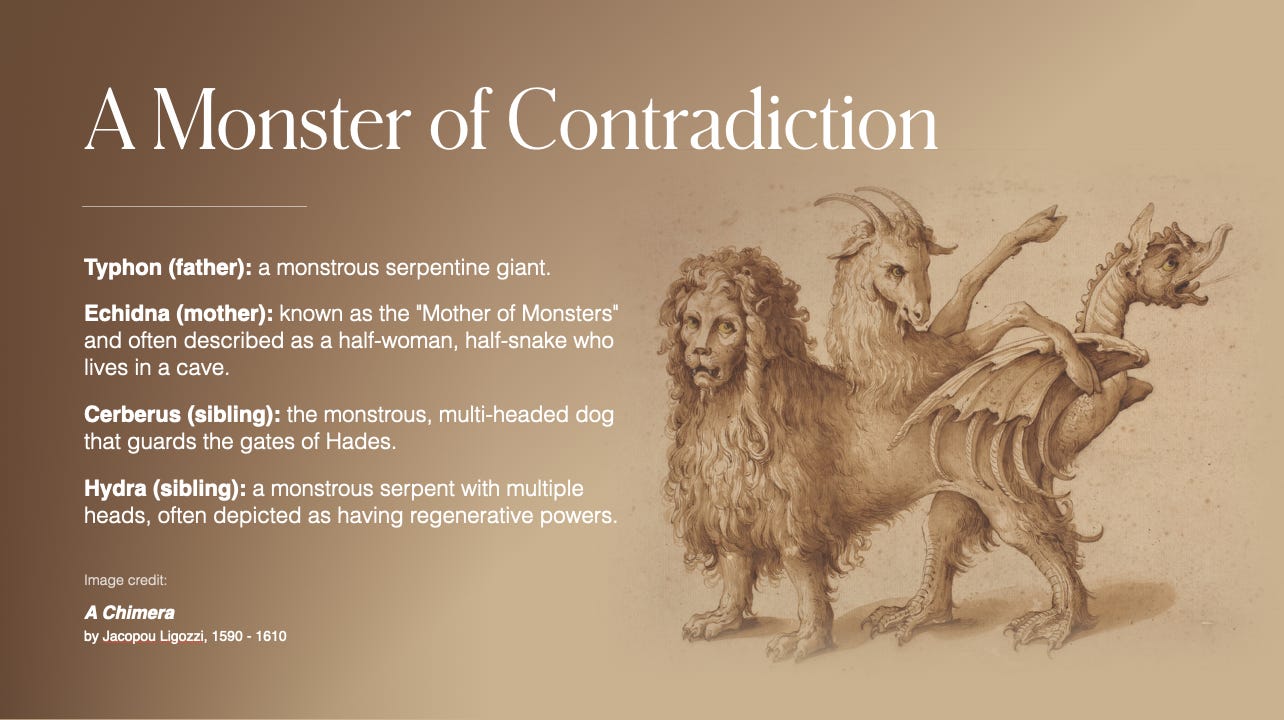

The Chimera comes from Greek mythology. It was the offspring of the fearsome Typhon and Echidna and a sibling of Cerberus – the three-headed guard dog of the Underworld – and Hydra – the also multi-headed serpentine monster slain by Heracles at Lerna, another entrance to the Underworld.

What I’m saying is that you probably don’t want to ask the Chimera for a look at its family portrait.

It’s worth noting here that the term “chimera” has come to describe any mythical or fictional creature with parts taken from various animals. So, these days, centaurs, mermaids, fauns, etc. are all considered chimeras with a lower-case C. In this post, we’re discussing the original Chimera, proud owner of a capital C.

The mechanics of monsterhood

In his book Monsters, David D. Gilmore describes the amalgamative nature of the Chimera – not one creature but a mish-mash of many – as a defining characteristic of monsterhood. In order to be monstrous, something must transcend boundaries: the Vampire, for example, is human plus animal (the bat, mainly, but sometimes the wolf); were-creatures obviously follow the same pattern; Zombies and Ghosts are both alive and dead; Witches and skinwalkers are both human and familiar, but also magical and superhuman.

As such, monsters are challenging in a number of ways:

Morally challenging – what is good, what is bad, where is the line between the two?

Cognitively challenging – what is real, what is make-believe, how do I know the difference?

Existentially challenging – monsters defy the rules, refusing to fit into the categories that provide us with a sense of normalcy, order, and therefore our comforting illusion of control.

In Gilmore’s words, monsters highlight “the arbitrariness and fragility of culture”.

What’s interesting is that we seem to have a fundamental need to be challenged in this way. No matter how uncomfortable this existential rugpull might feel, we crave monsters; dream of them; invent them as children; write them into our stories; and create them when they’re denied us (as discussed in the first episode of this series).

The Chimera, then, is the archetypal monster – the embodiment of chaos, contradiction, terror and confusion, born of a family of demonic beasts associated with death, darkness and the Underworld.

Monster as divine

Noting that the prevalence of monsters in art, literature and folklore grew exponentially with the genesis of monotheism, Gilmore discusses the “paradoxical closeness” of the monstrous and the divine.

Where God arrived to play the role of good, sacred, all-powerful father figure – the light – monsters possessed that same numinous mix of unnatural power, terror, and otherness but in darkness. In other words, monsters became the necessary shadow for the divine: awe-inspiring, chaotic forces that give shape to the concept of goodness by opposition.

To view this same theme from a psychological perspective, the monstrous is required for us to make sense of ourselves, what it means to be human, to be good, to be loveable, to be happy.

You, the Chimera

Of course, we are all chimeric in a sense. We cheerfully entertain the illusion of a constant, singular self – the self we refer to when we say “I” or “me”. But there is no singular “I” for any of us. We each shift and morph between versions of self from context to context and over the course of our lives.

We don’t like to acknowledge this, though. Just as with the Ship of Theseus, if we are rebuilt piece by piece over the years – beliefs, habits, preferences – what is there left at the end? Where am I in all of this? It’s super uncomfortable. So, we cling to the feeling of being the same vessel, charting a continuous course through time, even when presented with solid evidence that we are not the same people as we were in the past. In psychology, this is known as the end-of-history illusion.

“At every age, people underestimate how much their personalities will change in the next decade. And it isn’t just ephemeral things like values and personality. You can ask people about their likes and dislikes, their basic preferences. For example, name your best friend, your favorite kind of vacation, what’s your favorite hobby, what’s your favorite kind of music... To give you an idea of the magnitude of this effect... 18-year-olds anticipate changing only as much as 50-year-olds actually do... Human beings are works in progress that mistakenly think they’re finished.”

– D. Gilbert, ‘The psychology of your future self’ TED talk, 2014

Harvard psychologist, Dr. Daniel Gilbert, found that when people are given time to reflect, they can see massive differences between their current and former selves. However, when asked to project forward 10 years, people of all ages predict only small changes between their current and future selves.

Many parts

Our chimeric nature runs deeper than the big life changes of ten years’ time.

Inside, moment by moment, different parts of us take the wheel: parts with their own beliefs, skills, wounds and desires; parts of different ages, each trying to protect us in its own way.

You’ve probably heard yourself say things like:

“Part of me just wants to scream.”

“I hate how needy I feel.”

“I should be over this by now.”

“I don’t know what came over me.”

These moments show how it feels when contradiction rises to the surface. We don’t like it. We’d rather cling to the illusion of being one simple, consistent thing.

And so we spend decades at war with ourselves, trying to cut away the very parts that could make us whole.

The great irony is that this resistance – this effort to exile or amputate the pieces of us that don’t fit – is what makes them monstrous. The key is not to slay them, but to invite them in. To integrate them, just as the Chimera embodies its many selves.

So, is the Chimera really a devilish, fearsome anti-god, or is it a metaphor for the totality of self? An integrated whole? Is this monster, in other words, godly?

Order’s shadow

The reality is not that monsters are opposed to goodness such as order; internally, they’re at odds with the consistency illusion we like so much; and externally, with the directives of society and the simplistic rules we’re supposed to follow when it comes to who we are: be good, be strong, be certain, be reliable.

But real human beings are not that simple.

We can be kind and angry; hopeful and grieving; tender and ferocious; confident and ashamed; wild and wise.

We are everything all at once, but rather than embrace this, we flinch away from such paradoxes because they threaten our sense of control.

The chaotic soup of self

Control, control, control. This is the nub of it. The Chimera personifies our fear of losing control.

If I allow my anger, will it devour my kindness?

If I embrace my wildness, will I lose my reason?

If I admit my grief, will it drown my hope?

The unconscious self doesn’t think in binaries, and it isn’t afraid of contradiction. It’s only the conscious, rational mind that fears chaos – because when chaos abounds, we can’t even pretend that we’re on top of things.

So we squeeze our eyes shut, smooth out the edges, and try to flatten our nature into something neat, choosing the parts we like and cutting off the rest.

But integration doesn’t mean choosing one head and severing the others. It means letting every part have a seat at the table.

Internal Family Systems (IFS) & The Many Selves

In Internal Family Systems therapy (or IFS), we learn that each of the many parts that make us up has its own story along with its own ideas on how to keep us safe.

The angry part wants to fight.

The avoidant part, to flee.

The perfectionist, to achieve.

The wounded child, to weep.

None of these aspects of self is monstrous, but when ignored, repressed, or in the language of IFS, exiled… well, that’s when they roar, spit fire, spread their wings and loom larger than life.

I’d argue that this is what the Chimera exists to show us. Its message is an anguished, eternal cry for reintegration of resisted selves, and therefore acceptance of inner contradiction.

The chimera within

So, if it feels safe and comfortable to do so, I’d like to finish here by inviting you to consider one of your own contradictions.

For example, perhaps part of you wants to throw caution to the wind and move somewhere amazing, while another craves the comfort of familiarity.

Perhaps you see yourself as wild and carefree some days but reliable and mature on others.

Perhaps you both desire and dread something like competition or change, or perhaps you want to both quit and continue with a particular habit.

Take a breath, relax your muscles and open your mind. I’m going to present you with four incomplete sentences and I’d like you to see how your mind chooses to fill in the gaps. You don’t have to complete all four if one comes easiest, but of course you can if you like. Here you go:

Part of me wants to … but another part needs …

On the one hand, I see myself as … but on the other, I like to think of myself as …

Part of me wants to run from … but another part of me needs …

I find it hard to choose between … and …

If you can think of a contradiction of any of these kinds (or any other kind), imagine for a moment that on either side of the divide is a different part of the self. Then, if it feels okay, see if you can imagine an animal (or monstrous form) for each.

For example, perhaps the part that craves freedom looks like a bird or a flying fish, while the part that wants safety may take the form of a tortoise or hedgehog. The part of yourself you see as strong and dependable may look like an elephant, while the carefree dreamer might look like a unicorn or butterfly. You don’t need perfect representations. Anything that comes to mind will do.

When you have your two animals, take a moment to wonder how — if such things were allowed — you might combine them into one chimera.

It might be simple, as with a centaur or mermaid – half one thing, half the other.

It might be more complex, like the Chimera – requiring multiple heads and improbable anatomy.

Or, it might combine to become something totally different — a newt merged with a firefly becomes… a tiny fire-breathing dragon.

Obviously, there’s no right or wrong here – this is your Chimera, your imagination, you can do with it whatever you like.

When you have an idea, take a look at the fantastical beast you’ve created. Or, if you’re not a visual person, feel into it, sense it, imagine it in whatever way works for you.

It probably seems absurd, perhaps childish, funny. It might feel quite grotesque. All of these things are fine. More than fine, actually; they’re the point. The object of this little exercise is simply to allow this seemingly impossible thing to be.

When you have it, whatever it is, I’d like you to imagine that you can release your Chimera into the world. Whether you’d set it free to roam the tundra, to wander through the forest, to swim in the ocean, or to live in a city, or up a mountain, behind a waterfall doesn’t really matter, just that you give it a home – some kind of space to call its own.

The chimera in modern life

Lastly, as you imagine your Chimera in the wild — or as you just breathe and relax, if you haven’t followed the process — I’d like to leave you with the Chimera’s key piece of wisdom, which is that although the modern world exerts pressure on us to define ourselves neatly, the truth is messier and richer.

You might be a healer and a warrior; a skeptic and a mystic; a leader and a wanderer. And that’s okay. Your complexity is your power, not your flaw.

The process of individuation, according to Jung, is a lifelong journey of becoming more and more uniquely yourself, integrating every part, every shadow, every dream, every contradiction you come across as you grow. It’s not neat and it won’t ever be finished. Instead, it’s a living, breathing, ever-changing thing, just like the Chimera itself.

The journey’s end

So, with this, we have completed our epic journey through these ten meaningful monsters, each with its own vital message.

The Sea Monster posed the initial question: are you ready to face your own mystery?

Medusa taught us that our pain can become our strength when allowed to be seen.

The Vampire invited us to guard our life blood, and feed our souls fully.

The Witch cast a spell to help us trust our wild intuition even when the world finds it threatening.

The Dragon demonstrated that fear is the gate to transformation.

The Ghost whispered that grief and memory must be honoured, not exiled.

The Beast showed us that loving the shadow leads to liberation and wholeness.

The Werewolf howled that transformation and instinct are natural, not shameful.

The Zombie warned us against the death of spirit and called us back from numbness to life.

And now, the Chimera – the final monster, the ultimate monster – shares the ultimate truth: you are all of it. You are wound and wisdom, beast and beauty, shadow and light. And you are vaster, wilder, more magnificent than you were ever taught to believe, which means that you do not exist to be simple, but to be real – fully, messily, gloriously, and paradoxically alive.

And that is a magical thing.

References & Citations

David D. Gilmore, ‘Monsters: Evil Beings, Mythical Beasts, and All Manner of Imaginary Terrors’

D. Gilbert, ‘The psychology of your future self’ TED talk

Benjamin Hardy, ‘Who Will You Be in 10 Years? Not Who You Expect…’, published in Psychology Today

Richard Schwartz, ‘No Bad Parts’

Carl Jung, ‘Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious’

Carl Jung, ‘Psychology and Alchemy’

Have you heard about our new game Echoes?

Our new game Echoes is available for pre-orders on Kickstarter. It’s a futuristic tale of time travel, magic, myth and tarot, and it’s perhaps our favourite and most awaited project.

There’s a special card deck and other exclusive rewards available only on Kickstarter. Ready to meet the Selves, gather ancient wisdom, and save the future?

Thank you for this beautiful essay, it really dives into all the depths and corners of this archetype. Somehow I had to smile at the mention "the chaotic soup of self". I guess we're often trying to present ourselves as a nice 3-star meal with neatly separate and well digestible portions, but in truth, we're a stew and we don't recognise half the ingredients! :) I am both fascinated and frightened by the cimera and by the shapeshifter for a while, they feel fragmented and unstable, yet they also hold a quiet power: the power to hold many truths at the same time.

what a glorious journey this has been and what a beautiful way to complete the cycle! I truly loved it! Thank you!