The myth of inflated pride: This is how to love yourself better

A surprising lesson on how to live your life from the king of vanity himself

You can listen to this piece on TikTok, Instagram and YouTube.

***

What comes to mind first when you hear the word "pride", or when you imagine a proud or prideful person?

Pride is a confusing, double-edged sword. On the one hand, we're told to "have some pride" and to be "proud of our achievements." We see really important and powerful movements like Black Pride and Gay Pride, which encourage equality and the elevation of marginalised communities. Good.

On the other hand, we're also warned off pride from a young age when told that "pride comes before a fall", or that it is "at the bottom of all great mistakes." If we read the Bible, we'll learn that "The Lord detests all the proud of heart. Be sure of this: They will not go unpunished".

So, what's the actual deal with pride? Can we choose the good version instead of the bad?

The Myth of Narcissus: A Tale of Pride

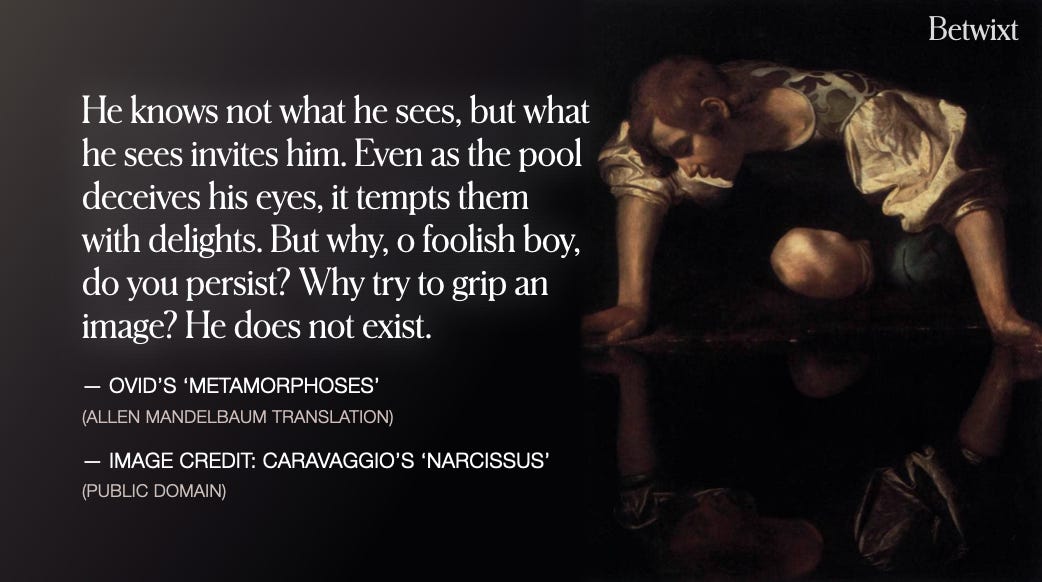

One of the most enduring myths associated with the "sin" of pride is the tragic story of Narcissus, a beautiful youth in Greek mythology who falls in love with his own reflection. This story, as told by Ovid in his Metamorphoses, goes something like this:

Narcissus – son of the river god Cephissus and the nymph Liriope – was renowned for his extraordinary beauty. Many fell in love with him, but he rejected them all. Among his spurned admirers was the equally beautiful and equally tragic character of Echo, a mountain nymph, cursed by the goddess Juno who'd angrily taken away her power to begin a conversation.

As a result, Echo could only ever repeat the last words someone else uttered to her. Having fallen deeply in love with Narcissus, Echo followed him around, reciting his own words back to him in a desperate attempt to connect. Narcissus, however, thought she must be ridiculing him and therefore shunned her.

One day, as Narcissus wandered through the woods, he came upon a clear pool of water. Leaning over to drink, he saw his reflection for the first time and was entranced by it. Unaware that the image was merely his own, he fell deeply in love with what he saw. Speaking to his reflection in the water, Narcissus said, “Your gaze is fond and promising; I stretch my arms to you, and you reach back in turn. I smile and you smile, too…” But when he tried to embrace his reflection, fingers disturbing the surface of the water, the image, of course, dispersed.

Narcissus eventually perished, dying by the water's edge. In some versions of the myth, the gods took pity on him and transformed his body into a flower—the narcissus, of course, which still grows by the water, bending down as if to gaze at its own reflection.

Echo, in her despair, also eventually fades away, becoming nothing more than a haunting voice to be heard in caves and other barren empty places.

In short, it didn't end brilliantly for either of these characters. So, what is this myth trying to tell us?

Jungian Analysis: Pride and the Shadow

In order to unravel the meaning of this story, we need to remember that the Jungian interpretation of archetypal stories like this one is that all individual characters and other elements of the world represent different aspects of the psyche, as opposed to separate entities. What this means is that Echo is a part of Narcissus's personality, just as Narcissus is an aspect of Echo.

So, while on the surface this myth can come over as a warning – a story about fate's direct punishment of a young man's unpalatable vanity – there's more to Narcissus than just conceit. To take an arguably better, healthier perspective on this tale, we need to consider how Narcissus grew so obsessed with his own image in the first place.

Such an obsession is, of course, not uncommon. Culturally, we elevate physical beauty far beyond what could be considered healthy or realistic, and this was apparently just as true of the ancient Greeks as it is of our society today. As an exceptionally beautiful example of a man, a character like Narcissus would have been continuously praised and adored on account of his looks. The problem with this is that the things we get praised for in life often become entwined with our fundamental sense of self.

A little like a child who's thrown into beauty pageants from age four, we can imagine that Narcissus grew up believing that his worth and appearance were one and the same – a still common misconception that disconnects us from both our true selves and others. A modern-day Narcissus would probably not stare into a pool of water so much as into the black box of his mobile phone, afraid to actually venture out into the world in case his real self doesn't live up to the perfection of his heavily-filtered Instagram reflection.

To make matters worse, when someone like Narcissus encounters their Echo-like admirers, the experience can be painful; that love, as superficial as physical beauty itself, reinforces the belief that we are valued only for such external qualities. In other words, that the rest of us – the real, deeper self – is invisible. That it simply doesn't matter. That we don't matter, unless we're pleasing to the eye.

What are we allowed to love?

So, what if, when Narcissus first sees his reflection in the water, he is not just captivated by his own beauty, but rather mesmerised by the only image of himself that he feels allowed to love?

What if this fixation on his reflection represents a desperate but misguided attempt to connect with himself, and find something inside that is worthy of acceptance?

Deep down he knows he wants more from himself than just that surface-level image. We see this when he tries and fails to reach through his reflection and find something of substance. We also see this in his rejection of Echo as someone who can only ever reflect Narcissus back to him with her echoing words. Narcissus wants more – needs more – from himself and from others, but he just can't get a hold of it.

The Narcissus in each of us

Viewed through a Jungian lens, then, Narcissus represents the part of the personality that believes one's worth is based on external, objective things or achievements. We all have this part, to varying extents, although it won't always be focused on physical beauty. For some of us, our most desirable reflection will be made of achievements, accolades, power, wealth or possessions. And is it not tempting to believe in the reality of these effigies? Is there not a weird kind of comfort in believing that if we just tweak that image until it's as perfect as it can be, that we will then feel a tangible sense of worth?

All of a sudden, the vanity of Narcissus feels altogether different.

Echo as Anima

And what about Echo? When viewed through this lens, her part in the story also transforms. Instead of being a mere victim of unrequited love (or worse, a vacuous, infatuated pest of a woman), Echo can be seen to represent a most vital part of Narcissus that he is unable to reach. That is, the anima or soul; his true self, repressed emotions, and genuine need for connection and love beyond the superficial.

Echo’s curse, which is also Narcissus' curse, reminds us of how unacknowledged, unexpressed emotions and needs forever fail to be satisfied. Instead, they echo back to us, perpetually, unheard and misunderstood.

Ultimately, Narcissus’ inability to acknowledge the love and connection offered by Echo leads him to slowly waste away — a metaphor for the spiritual and emotional death that can result from buying into the fantasy that true worth can be achieved by perfecting the version of self we show the world.

Using this story for personal growth

This more empathetic take is a much kinder way to read the myth of Narcissus, but it still sounds a bit like a warning more than anything else. So, is there even a good side to pride?

Yes, there is. Just as Narcissus' disconnected end in this story can be seen as a warning of the dangers of exaggerated pride, Echo's fate can be seen as a cautionary illustration of what awaits us if we go the other way – if we relinquish self-interest so entirely that we direct our love exclusively outwards and onto others.

Healthy pride, then, must exist somewhere between these two extremes: a balanced version of this energy that allows us to love both ourselves and others.

The two faces of pride

In psychology, this healthy pride is known as authentic pride. It's the positive counter to hubristic pride, which is of course what we see with Narcissus. Let's break these two terms down.

1. Hubristic pride

Hubristic pride, which is experienced when we have an over-inflated sense of self-importance, is actually adaptive. It enables us to obtain dominance and power, which in the hierarchical social system that is the human race can sometimes be necessary, helping us to win important resources that mean we're able to feed and clothe ourselves, etc. However, hubristic pride is an ineffective means for achieving good relationships or general happiness.

2. Authentic pride

Authentic pride, on the other hand, is more realistic and allows for the appreciation of other people around us. In order to feel authentic pride, we don't need to feel better than others. On the contrary, this is an eyes-open type of pride that feeds on connection and enjoyment of others in our lives.

It's important for healthy drive and self-esteem, motivating us to persevere even in the absence of external incentives. It therefore supports the pursuit of positive and value-aligned goals. In other words, we need this kind of pride in order to live a life of meaning, purpose and connection.

Reference: Carver CS, Johnson SL. Authentic and Hubristic Pride: Differential Relations to Aspects of Goal Regulation, Affect, and Self-Control. J Res Pers. 2010 Dec;44(6):698-703. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.09.004. PMID: 21769159; PMCID: PMC3137237.

How to choose authentic pride

How do we choose the latter? The key difference between these two types of pride comes by way of integration, self-awareness and healthy contextualisation.

We get the dark side of pride – hubris – when we close our eyes to it, brand it as bad and force it into the shadowy waters of the unconscious. When we do this, we can find ourselves enslaved to a devouring sense of unacknowledged pride, which shuts us off from the world and inspires toxic, competitive behaviour.

If we work to bring pride out of the shadow and into the light of conscious awareness, however – if we work to accept and integrate it – then this aspect of self can bloom into something of great worth: authentic pride.

So how can you bring your pride out of the shadow?

Own your pride

In a practical sense, doing this means taking the time to observe and reflect on our thoughts, emotions and behaviours, and resisting the urge to quickly sweep any signs of hubris under the carpet. Counterintuitively, it requires that we acknowledge and own the things we feel proud of, rather than batting compliments away or downlpaying our success.

Acknowledge the help you've had in life

But that's not enough on its own. We also need to acknowledge the help we've had along the way. This point is key. A big part of this alchemical process must involve diligent and often challenging contextualisation of ourselves in relation to the rest of the world. If we fail to acknowledge our privilege – be that of class, gender, race, position within our family or extended social circles, or any other advantage – then we run the risk of inflating our own self-image to the point where it becomes a problem.

To remain connected and awake is to stay grounded in our pride. Honouring the input of others doesn't diminish our success. On the contrary, it expands it, because then we get to feel proud not just of ourselves but of those around us too.

Align your pride with your authentic sense of self

And, finally, we need to align our personal pride with authentic meaning. If we take pride in the parts of our lives that correspond with our values and what gives us purpose – rather than trying to find it in the things we're conditioned to value (like beauty, wealth and power) – then pride can drive us forward in a way that leads to more connection and a more meaningful existence.

A different fate for Narcissus

If Narcissus had been able – nay, allowed, or at least encouraged – to see beyond the superficial beauty that the world told him was the source of his worth, then he would surely have found other parts of his life to feel proud of. If he had been able to access self-love, and in turn receive the love of others, then he may have been able to tear himself away from the projected image of perfection to which he was so wedded.

The same goes for us, too. If we want to integrate the volatile potential of pride so that it serves rather than hinders us, then we need to choose to look beyond our superficial personas. We need to stop depending on our looks, achievements, qualification or our carefully curated Instagram profiles for a sense of meaning or worth. Because no matter how great those things might look, they can never offer anything more tangible than a rippling reflection.

I wonder what this might mean for you?

Thank you for reading!

We’re Hazel (ex boxer, therapist and author) and Ellie (ex psychology science writer). We left our jobs to build an interactive narrative app for self-awareness and emotion regulation (Betwixt), which you can try on Android here and on iOS here.

Very helpful explanation of healthy pride 😁

Always a pleasure having you muck about in the noodle soup, showing me where to detangle my noodles. Thank you, Haz!Looking forward to the rest of this series.