The Myth of Insatiable Gluttony: What overindulgence can teach us about what it means to be human

Why can’t we stop? The hidden meaning behind our cravings

Have you ever eaten past the point of fullness and wondered… why am I still doing this?

Have you ever trained, worked, drank or binged on TV for longer than you needed?

Gluttony in one of the so-called deadly sins, but as self-destructive as it may seem, the psychology of overindulgence is not that simple. Today, we’re going to explore gluttony as a psychological signal. A clue into what we're really craving and how to meet the need. And we’re going to start with a myth about eternal, insatiable hunger.

The Tale of Tantalus

King Tantalus – from whose name we get the word "tantalise" – was favoured by the gods and often invited to divine dinner parties on Mount Olympus. Despite this privilege, though, Tantalus was arrogant and ungrateful, and he used his time with the gods to learn their secrets and steal divine food, both of which he shared among his mortal friends in order to prove his own superiority. What a guy.

The most infamous of Tantalus’s crimes was a grotesque attempt to test the gods' omniscience. One day, he killed his own son, Pelops, cooked him into a stew, and served him at a banquet to see if they'd notice. Other than Demeter who, distracted by her grief, consumed a piece of Pelops's shoulder, the gods knew what was being served up. Enraged by his arrogance, they punished Tantalus.

Zeus cast him into the Underworld where he was made to stand, for eternity, in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree. Whenever he bent down to drink, the water would recede. Whenever he reached up to grab the fruit, the branches would lift higher, keeping it forever out of reach.

Parched and ravenous, Tantalus remains there today – surrounded by abundance but never able to satisfy his ravenous desire.

Tantalus as a symbol of gluttony

Tantalus, in fairness, represents more of the deadly sins than just gluttony – he's hubristic (pride), envious of the gods, and greedy for power, too. I chose his story for this article because Tantalus's punishment serves as such a poignant representation of what it feels like to be in an addictive cycle – compulsive eating, drinking, gambling, exercising, etc. – where, no matter what we do or how hard we strive, true satisfaction always remains just out of reach.

So, what's going on with this? Why do we get into these impulsive, obsessive and self-destructive habits, and what can we learn from the fate of Tantalus in order to avoid these binds?

Why we overindulge

In terms of food-focused gluttony, part of the problem is that our brains – which evolve much slower than the world around us – are wired for a very different kind of life. We are neurologically programmed for a time when food was scarce and storage difficult. In other words, our brains still think it's a good idea to eat as much as we can whenever food is available. Neurologically, the drive for food involves dopamine (the want more neurotransmitter), and enkephalin, which is an opioid receptor. These two things combined make food and eating highly addictive, which is necessary, of course, but also potentially problematic.

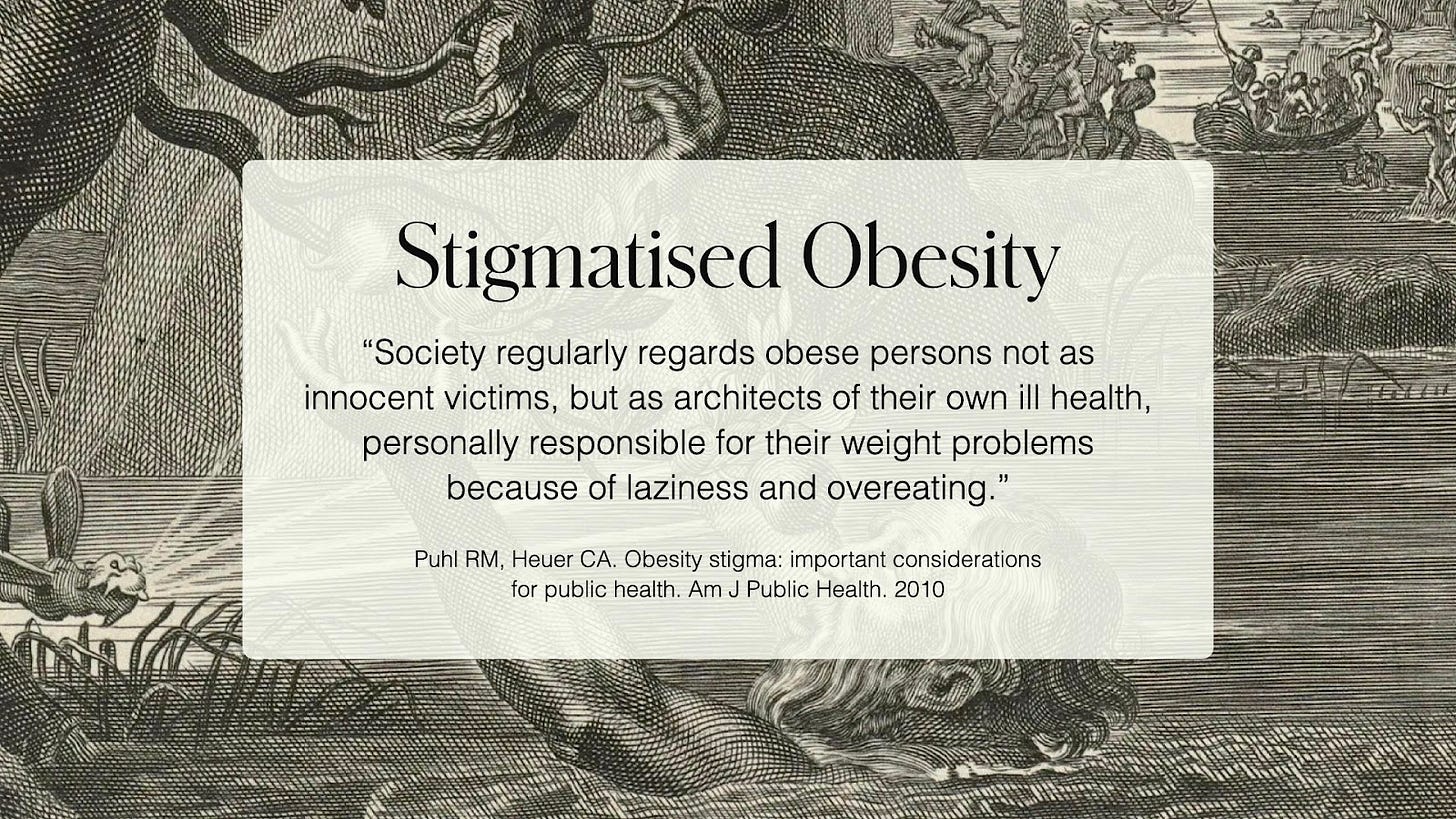

Overeating and obesity are hugely stigmatised in our culture. We judge those we see as overweight harshly, rapidly and unfairly.

Stigmatised obesity

Studies show that the stigmatisation of obesity is linked to the perception of personal responsibility. People perceived as overweight are assumed to be lazy, weak-willed and gluttonous – which, as we'll explore, is not necessarily the case. To make matters worse, these harmful prejudices are commonly dismissed as acceptable and even necessary, a viewpoint driven by the assumption that obesity is de facto under personal control and those who struggle with it just need a good kick up the backside.

At the heart of all this is another dangerous assumption: that eating is inherently pleasurable and that those who eat more than we might consider necessary are therefore impulsive hedonists who can't keep their urges under control.

However, neuroimaging of both obese and non-obese brains, says author Mark Schatzker, shows this pleasure-seeking assumption to be false. Not only do obese brains create a much, much more powerful craving for food than non-obese brains, they also experience dampened levels of pleasure from eating. In other words, obese people will experience less joy from drinking a milkshake than non-obese people, but they'll still be driven to do so by an automatic obsessional craving that makes the milkshake feel like a matter of life or death.

What this means is that it just does not make sense to brand people who struggle with their weight as weak-willed, lazy or hedonistic, and doing so is more likely to exacerbate the problem by isolating and ostracising people who need care and connection, not discipline.

The Existential Escape Hypothesis

Of course, it's not only people in the obese category who overdo things. Enter the Existential Escape Hypothesis, which in the words of Dr Andrew Moynihan states that "when people experience a threat to their sense of meaning in life, they might engage in gluttonous behaviour as a way to escape from that experience."

The act of eating (along with other bingeable pastimes like watching TV and even exercising) only demands basic, evolutionarily old mental processes. This means that disappearing into the trance-like state produced by these activities gives us respite. We get to temporarily switch off from the pain, dread, confusion and uncertainty brought on by big difficult experiences like trauma and grief, and also objectively smaller forms of discomfort like boredom, loneliness, and the inescapable reality of our mortality.

So, when something threatens our sense of meaning, purpose, connection or our very existence, turning to food, drink, gambling, working out, or pretty much anything else we've made a habit out of, can be seen as a solution – it's a temporary and ineffective one, but a solution nonetheless.

The Bigger Picture: Tantalus through a Jungian lens

Returning to today's myth, what if we were to see Tantalus’s actions not as malicious, greedy impulsivity, but as a reflection of a profound, unacknowledged hunger?

Tantalus lived in a kind of liminal space between the gods and mortal men. Viewed through the lens of Jungian psychology, the gods can be said to represent the divine perfection of the Self – the wholeness and completeness towards which we may strive but will never truly experience in our human lifetimes.

Stealing the ambrosia and nectar, revealing divine secrets, and even the grotesque act of sacrificing his son, could all be viewed as Tantalus's misguided attempts to bridge the gap between his mortal limitations and the divine perfection he so craved.

Hunger for more

We all know what it's like to find ourselves reaching for satisfaction that proves to be forever out of reach. For most of us in the West, it's not basic needs like food and drink that we can't get our hands on, but the deeper, more slippery needs of love, connection, self-worth. Wholeness.

We say to ourselves: if I could just win that award, publish a bestseller, lose ten kilos, or start making 6 figures… then I'll feel enough. But, if and when we meet our targets, the satisfaction is disappointingly short-lived because we quickly realise the accolade, money, beauty or prestige does not deliver inner enoughness. Just like Tantalus, we find ourselves in a perpetual state of wanting and needing more but having no real way to get in touch with it.

Tantalus's final predicament, then, serves as a potent metaphor for this kind of inner psychological disconnect between the ego or the conscious, thinking self, and the shadowlands of the unconscious – and therefore unmet – needs, values and desires.

Self-sacrifice

In the myth, the smaller transgressions of theft and divulgence were overlooked by the gods – we're all allowed to make mistakes. It was only when Tantalus sacrificed his own son in an attempt to outfox the gods, and therefore level the playing field, that they took action.

Pelops, here, can be seen as a representation of the Child archetype, symbolic of hope and transformation. His sacrifice, therefore, marks the moment when Tantalus loses hope; when he loses himself to the pursuit of more. It was this that was punished, and this that led to Tantalus's eternal state of unsatisfied hunger.

Applying this to our own lives

The good news is that Pelops was resurrected by the gods, and his shoulder replaced with ivory. He went on to be a chariot-racing king, beloved by Poseidon. So, although Tantalus's story seems to end in such misery, his essence and hope did live on. And ours can, too, no matter how deeply we might feel we've fallen into any kind of gluttonous cycle.

In much the same way as we discussed in the article on greed, the way to alchemise gluttony is to see if we can start channelling it in better ways. I'm not suggesting it's easy and I'm certainly not proffering a cure for obesity (that would be a whole different conversation and one that should be had with a medical doctor). But there are ways to think about our cravings and habits that could stymie the Existential Escape Problem and allow us to take back control of our self-destructive patterns.

Moynihan suggests that actively seeking and choosing to engage in activities that bring us a sense of meaning can stave off the existential dread that may otherwise lead us into mindless escapism. Whether we find meaning in music, art, movement, connection, philosophy, acts of service, or whatever, it may be possible to swap our self-destructive binges for deep dives into things that actually matter to us. And, the more we do those things, the better guarded we'll find ourselves against the threats of boredom, loneliness and mortal dread going forward. In theory, the positives should snowball.

But, of course, life throws curveballs, too. We will all struggle along the way, and we may turn to addictions and dependencies during those times. I would hope that awareness of what's going on in these situations may help us find our feet faster as we heal. I also hope it may help us to empathise with others when they are struggling.

Although I must repeat that I'm not touting this as a cure for addiction, obesity or any other serious condition, I would urge you to consider this final thought:

What if your cravings conveyed a deeper message? No matter what it might be that you gravitate towards, consider when and where cravings surface for you and then ask yourself what's really missing in those situations.

To seek meaning is to seek a life of fullness, authenticity and self-connection. This will rarely be the easy way out, but in the long term, it will almost certainly be the better choice.

***

References:

Evolutionary anthropologist Dr Anna Machin from the Department of Experimental Psychology at the University of Oxford, speaking on BBC Sounds' Seven Deadly Psychologies: Gluttony.

Puhl RM, Heuer CA. Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health. 2010 Jun;100(6):1019-28. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.159491. Epub 2010 Jan 14. PMID: 20075322; PMCID: PMC2866597.

Food writer Mark Schatzker, author of 'Steak', 'The Dorito Effect' and 'The End of Craving'

Dr Andrew Moynihan from the Department of Psychology at the University of Limerick

Thank you for reading!

We’re Hazel (ex boxer, therapist and author) and Ellie (ex psychology science writer). We left our jobs to build an interactive narrative app for self-awareness and emotion regulation (Betwixt), which you can try on Android here and on iOS here.