What lurks beneath: The meaning of sea monsters

This is what a giant demonic octopus can teach us about the self, the shadow and the patriarchy

You can listen to this piece on YouTube.

***

First, the water shifts. Then, silence. A shudder moves through the hull.

From the deep – where sunlight cannot reach – something vast begins to rise. A shadowy tangle of limbs and teeth and huge, all-seeing eyes.

The Kraken, the Levianthan, Scylla and Charybdis, Umibōzu… The sea monster goes by many names, but it always inspires dread, horror, awe. It is always very, very big. As an archetypal beast, its meaning is equally mammoth.

The Sea Monster Archetype

Accounts of sea monsters are found in virtually all cultures with a connection to the sea — their presence in the waters of human imagination, in other words, seems pretty much inevitable. In myth, this common archetypal symbol tends to represent primal, chaotic forces in the world's creation or the embodiment of the unknown, unpredictable, mysterious and dangerous.

Examples of sea monsters include:

The Leviathan, a large sea serpent or whale-like creature from Jewish mythology, often associated with chaos and destruction.

In Greek mythology, Scylla and Charybdis were fearsome sea monsters guarding the strait of Messina. Scylla, with six heads and twelve feet, resided on a cliff, while Charybdis, often depicted as a monstrous whirlpool, lurked opposite her.

Umibōzu from Japanese folklore, is often described as a giant, shadowy, human-like being that rises from the sea to capsize ships, particularly those of sailors who disrespect it.

And of course the Kraken, a massive, squid-like creature from Norse mythology, also known for attacking ships.

The forms sea monsters take vary – some tentacled, some humanoid, some serpentine – but they all share one important thing: they rise from below. From the unseen, the unknown, the uncontrollable.

The Depths of the Psyche

In Jungian psychology, the archetype of the ocean, sea or any deep dark water represents the unconscious mind and the shadow.

Sea monsters, then, represent the fears, urges, memories and truths we’ve thrown overboard, but which still stir below the surface. Because, no matter how much we'd like to delete or slay our most painful, uncomfortable or unpalatable thoughts and feelings, it isn’t possible to exterminate an aspect of the self. Instead, within the mysterious and terrible soup of those unconscious waters, resisted parts of the self mutate into monsters.

Sea monsters are the ultimate symbol of what we fear will consume us. They are the panic attacks that come without warning, the grief we thought buried that surfaces in other ways, the shame that casts a menacing shadow everywhere we go, the unmet need that devours and devours, forever attempting to find fulfilment that it cannot reach.

Myth & Meaning

In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus must sail between Scylla (the many-headed devourer) and Charybdis (the whirlpool that swallows everything). To survive the journey, he has to reckon with both monsters – not to defeat them, but to navigate between them.

He chooses to sail closer to Scylla, who devours six of his men, rather than risk losing the entire ship to Charybdis's whirlpool. So, as opposed to the more obvious (and in my opinion less helpful and less interesting) proposition of a direct victory over the monsters, Odysseus' encounter speaks of the impossible choices and inevitable sacrifices inherent in any epic journey.

As such, the story serves as the perfect metaphor for what it means to move through the inner chaos we must willingly walk (or sail) into when going through a challenging experience, or when processing pain or trauma in therapy, for example. On journeys like these, things will be lost: old beliefs about the self and the world, coping mechanisms, habits, dreams, versions of self. And while it may feel like obliteration looms, with courage, caution and conscious decision-making, we don't need to be consumed when we make these passages.

The mother monster

Often, sea monsters are depicted as female. This is not a universal truth – the Kraken is androgynous (not assigned any gender) and although Umibōzu is said to take the form of beautiful women to lure sailors to their death, the monster is usually described as male.

However, both Scylla and Charybdis are portrayed as female. Particularly in earlier Jewish texts such as the Book of Enoch, the Leviathan is described as a female sea monster. Lesser monsters of the sea also tend towards femininity: mermaids, sirens, and the Nereids (or sea nymphs) were all originally female.

The prominence in myth of dangerous female sea monsters (and any other female monsters, really) may reflect social anxieties about feminine power and sexuality. Within a patriarchal world, such as ours, femininity is de facto forced into the collective shadow and feminine forces – emotion, intuition, chaos and creation – are cast in a monstrous light. What's more, for a patriarchal structure to sustain itself and remain unchanged, that rejected femininity must stay beneath the surface, lest it rise up and take the system down, pillar by pillar. Historically, then, sea monsters may have served as warnings about the potential dangers of female influence or transgression. Stacks up.

"It was in the Middle Ages that the Sirens were re-imagined in their familiar form of half-fish mermaids, who still retained their infamously alluring voice; this trait was already established in Homer’s Odyssey, where the eponymous hero is asked to be tied to the ship’s mast in order to resist the Sirens’ deadly song. This particular attribute is deeply gendered, since the Sirens’ danger lies in their having a voice, contrary to patriarchal gender conventions: their ability to sing literally causes death, thus encapsulating the male fear of allowing women to speak in public."

– Lamia, Sirens, and Female Monsters: Feminist Reframings of Classical Myth in 19th-Century Literature, Posted on 31st March 2022 by Nina Triaridou, Antigone journal ⠀

Take the Sirens' deadly song, for example. As Nina Triaridou argues, "the Sirens’ danger lies in their having a voice, contrary to patriarchal gender conventions: their ability to sing literally causes death, thus encapsulating the male [i.e. patriarchal] fear of allowing women to speak in public." Around the time of those myths' first tellings, women were not meant to tell their stories, and so instead, stories were told about the importance of silencing them.

“When the Sea came to our village, she was an old woman. She arrived when the water crested and draped over the earth, its salty fingers pushing out offerings of sea glass and bladder wrack. Her dress trailed behind her, hair tangled with kelp and tentacles. No one doubted that she was the Sea. Everyone was disappointed."

– The Day of the Sea by Jennifer Hudak

However, the femininity of sea monsters is also connected to the fact that the ocean is usually coded as feminine (e.g. "the sea is a cruel mistress") and all that traditionally, water is a feminine archetypal force along with the moon, soil, and caves, as opposed to the masculine symbols of the sun, fire, sky, and mountains. Equally, darkness, emotion, intuition, the unconscious, and chaos are feminine, as opposed to their masculine counterparts of light, logic, reason, the conscious mind, and order.

Again, because we live in a world that venerates the masculine side of all those polarities, the deep feminine does sound like a scary proposition.

And it is, but it's also the home of transformation, connection and relatedness (as opposed to the masculine focus on stability, individuation, and separation).

Ultimately, we need both forces. If we allow the feminine to stay in the shadow – if we continue turning away from our emotions, intuition, and our quieter needs for self-reflection, mystery, even chaos – then we are inviting the Leviathan, Scylla and Charybdis into our worlds, along with other watery beasts like the Kraken (or the Kra-Karen if you've read the Dungeon Crawler Carl books, which was a reference I enjoyed greatly, and one that paints a brilliantly modern picture over everything I've just been talking about).

Patriarchal values encourage us to be the constant hero – to strive for outer strength and success and the shiny achievements that result from slaying weakness, vanquishing enemies, and just… doing – but we can't stay in that mode indefinitely. As with pretty much everything, balance is key. Just as the tide advances and withdraws in an endless cycle, a life of wholeness and growth will also oscillate between feminine and masculine energies: periods of individuation and self-assertion are followed by periods of integration, reflection and connection, and on and on.

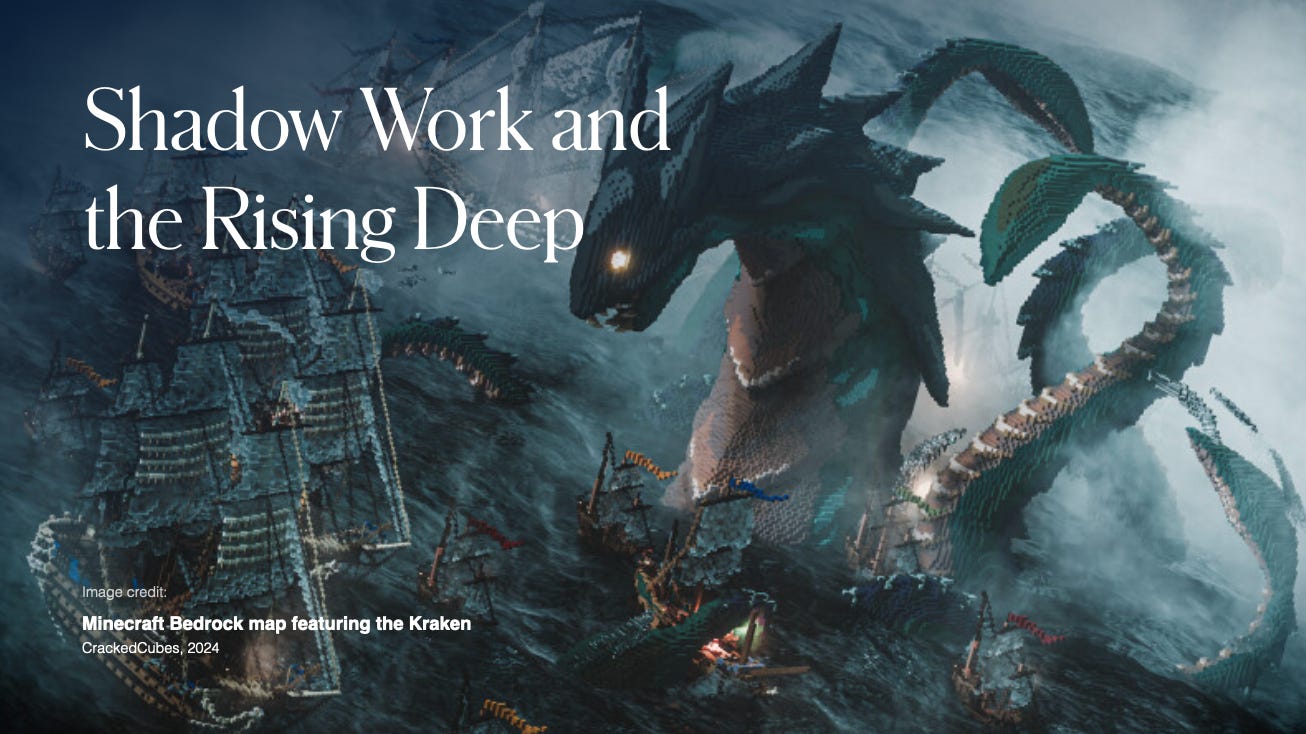

Shadow Work and the Rising Deep

So, we all need to take a deep breath and face our sea monsters at some point. If we insist on sailing smooth, shallow waters – living only at the surface – these monsters will catch us off-guard. But if we dare to look down, to meet the beasts below with curiosity instead of fear… that's when things can change.

Over the course of this series, we're going to meet monsters of all kinds: Medusa, the vampire, the witch, the dragon, the shadow beast, ghosts, werewolves, zombies and the Chimera. Each has its own lore, its own wisdom and its own challenge to take on.

Welcome to the deep

Here at the very beginning of the journey, it's the sea monster's challenge that we must face: are we willing to wade into the water? Are we willing to brave a look into the depths?

If it's safe to do so, close your eyes, then take a deep breath and imagine that you’re standing at the edge of the world – a cliff overlooking the midnight ocean. Salt air fills your lungs. You can hear the crash of waves breaking far below. The moon hangs huge in the air, its silver light turning the water to mercury.

Somewhere in the distance, something moves beneath the surface, and you don’t need to see it to know that it’s vast. But you step forward anyway, and begin to descend – down, down the crumbling path that leads to the rocks, slick with saltwater.

Then, as you kneel at the boundary between land and sea, the waves still – the water becoming a black mirror. And as you look into that mirror, you find a face staring back. It's yours, at first, but then it shifts – becoming strange, suddenly: older, wilder, eyes gleaming with wisdom, with grief, with power, truth, and with everything you've ever rejected, too, everything you've tried to forget or disallow.

Looking deep into those eyes, though, I wonder if you feel not repulsion or even fear, but… something else. Something with more promise, more purpose. I wonder if you can feel that this monster is not separate from you, never was, and never needed to be, either. Not really.

So you breathe and you do the only thing you can: you let it rise, let it speak, and you listen to the song it sings.

Now, I can't tell you what you may hear within that melody if you listen for long enough; whether you’ll remember who you were before these parts of you were silenced, before the storm, before the forgetting; whether you'll hear a plea or a warning or a cry of strength; or whether, for you, something different will surface. But, no matter what it offers, I can tell you that your mission is not to banish the monster. None of us is on that path. Instead, our quest is to welcome it home.

So, as you pause there by the water’s edge for just a moment longer, face to face with this dark being, I'd like to ask if you can sense this simple thing: that the work has already begun.

I'll leave you with that, and I hope to see you for the next episode in this series, where we're going to meet the queen of rage herself: Medusa.

You are such a story teller!!! I love the depth and care you put in the content ❤️

as a sea lover, it's really exciting to get to know sea monsters under this light. Thank you for the work you put into these, they're a wonder to read. Balance is key, I totally agree on that. We cannot only count on one, we need both masculine and feminine sides working harmoniously, that inner wholeness is what we can strive for.

The ending "welcome to the deep" is absolutely wonderful. When I read this line, the word that came up for me is love: "Looking deep into those eyes, though, I wonder if you feel not repulsion or even fear, but… something else." Because love is the strongest, most powerful and healing force in this universe... the main ingredient, source and fabric of this whole existence... And I do believe that when it feels taken away, things wither and take a shape that lacks harmony and portrays what we call "monstrosity". Good thing it all can be transformed!

Again, keep up the good work and have a very blessed week-end!